On Using Original Languages in Sermons

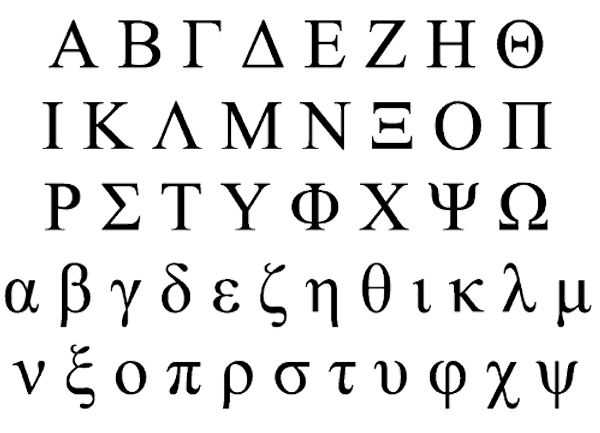

Confession time: I have never taken a course in Greek or Hebrew. While I have “picked up” quite a bit in my studies over the years, I have never done what so many other preachers have done. Many has studied the Biblical languages (especially Greek) in a systematic way through classes and even work through their own translating of the text when they study for a sermon.

Confession time: I have never taken a course in Greek or Hebrew. While I have “picked up” quite a bit in my studies over the years, I have never done what so many other preachers have done. Many has studied the Biblical languages (especially Greek) in a systematic way through classes and even work through their own translating of the text when they study for a sermon.

I do study in the languages, though. While I am not (yet!) able to “go deeply” into every word and phrase, there are plenty of tools at my disposal that help me get more out the text as a I study for a sermon. I enjoy each time I am able to discover some new nuance to a word or phrase and love putting that knowledge with other information to gain deeper insights into the text.

As a preacher, though, one of my struggles is how to “work in” Greek and Hebrew words/phrases into a sermon. I have sat through some sermons where it seemed as though every other sentence contained a Greek word. Some preachers just use the words with no explanation, and people like me (without training in this area) might have no idea what he is talking about. Others go to the other extreme and never even so much as mention the original language.

As one who loves the study, but has not been through the “classical training,” I try to share with the listeners what I have learned. Sometimes I do give the word or phrase from Greek or Hebrew, but always with an explanation as to what it means. I also try to “boil down” the definition to the simplest terms I can. If the word/phrase is a word picture, that can be shared in a beautiful way with some practice.

I also try not to “load up” a sermon with these references. I don’t want the sermon to sound like I’m reading a dictionary. Instead, I want to convey one or two key words or phrases to the listeners that will impact their knowledge of God’s Word and their trust in the text. For example, we finished a series on Psalm 23 this past Sunday. Of course, we were studying verse 6, so I took the time to share what the original Hebrew words that are translated “goodness” and “mercy” mean (since some translations have slightly different terms). I also took a moment to share that the word “forever” is actually from a Hebrew phrase that means “for length of days.” While the difference may seem subtle, it adds a great deal to the study of the text.

Preachers need to make it a lifetime pursuit to know as much about the original languages as possible, because they will then be able to “mine” great “gems” from God’s Word. Working those findings into a sermon, though, requires a lot of prayer and thought.

————————————————-

What are your thoughts on using the original languages in sermons?

10 Comments

Scott

I agree with the way you use Greek in lessons. I usually only reference the actual word when the word sounds like a word we use in English that is similar to help people remember that word or concept. Otherwise, I might mention that I “understand the original word to communicate the idea of . . .” without ever attempting to pronounce the original Greek word.

I think many church members, while impressed with a speaker’s knowledge of Greek or Hebrew will shut them out as arrogantly displaying their education if they repeatedly spout original languages.

Justin Guin

It all depends on attitude. When you mention Greek it must be done with great humility. We are all students of Greek and Hebrew not authorities on it. I have been blessed to take 5 semesters of Greek and love to study it. However, I rarely use the phrase, “In the Greek it says…” in lessons and sermons. In my opinion most people don’t care what it says because usually what you say is represented in their English translations. Most English translations are very good. What I try to do is give the fruits of my study without using technical language. I try to deepen understanding without making the audience feel like they are hearing a reading from a Word Biblical Commentary. Greek is a tool for study and understanding not boasting one’s ego. My rule is this: If the nuance will help them with everyday life then use it. If not then I dont mention it. Great post. Keep up the good work.

Dwight Whitsett

The overarching purpose of preaching to the disciples is to give them something practical to facilitate, encourage and equip them to live as Christ in our culture. Whether it is injecting a Greek or Hebrew word, telling a joke or using an illustration, it needs to pass the test of practicability. We are not up there to look good (thank goodness)or sound good. But then, we all know that already, don’t we?

Jay Lockhart

Your approach to using the original languages is right on target. Words like ekklesia, agape, and baptizo are words most people who have been in the church for a long while know and I do not hesitate to use them. Most of the time I do not mention the original word, but simply say, “The Hebrew (or Greek) word means…” or “The original word is a compound word made up of…and … and means….” Sometimes this allows for an additional insight into a word that is important and may be helpful. A preacher who works with a church near a college campus may put extra pressure on himself by thinking that the PhD’s in his audience want a technical sermon filled with this stuff, but as one college professor told me, “When I hear a sermon I am not interested in hearing a college lecture, but I want a simple message that helps me grow in and live for Christ.” That’s what most people want and need…I think. Keep doing what yur are doing!

Jay Lockhart

Wesley Walker

I think original languages need to be a heavy part of the sermon. I’m not for sure if you can use them too much (this could simply be me defending the amount of time and money I’ve invested in being trained in them). But I think the time to use them is in preparation. Do good word studies. Look at syntactical relationships. Re-translate the passage and bring that wealth of knowledge you have unlocked into the pulpit. But there is no need to say the Greek says this, not that. Or this Greek word is this and means this. Or the Hebrew implies this, not that. At times this is helpful, but do it too much and people begin to believe that they cannot understand Scripture without first knowing the languages. Instead just make the statement without disclaimers.

That being said with today’s technology preachers need to be using the original languages in appropriate ways (sadly many preachers use the original languages in ways that distort more than explain)today.

Dayna Zoll Cookson

I think these gentlemen are right on target on their use of Greek in sermons and sermon preparation. I too studied Biblical Greek for 2 years in college and was told – use the Greek to better interpret the Word and preach/teach better; do not use the Greek in your preaching/teaching unless absolutely necessary. As has already been mentioned, using Greek in a sermon must be approached with humility and can easily be offputting to listeners. I would hate to think I lost someone’s attention and they missed the point of a message or lesson just so someone else could better understand the “true” meaning of a particular Greek word.

brian

I haven’t kept up my greek studies since school, but try to restart occasionally.

I only mention something if it really makes a difference.

since I preach out of NIV, i point out what words are added.

While preaching on the I AM statements of Jesus, i mentioned that pronouns (I, you, we, etc) are used for emphasis in Greek, and that’s the case in Jesus’s statements in John,

little stuff like that occasionally can make a sermon better, but weekly mentioning of greek words, or worse, grammar, is not usually helpful or necessary in my opinion

I think more importantly, is that our people understand that it was written in Greek, and a little something about translation so they don’t use only one Bible, or idolize one translation

Pingback:

Bill Wolfe

When at DLU, 85-88, I focused on all of the ministry classes (pulpit, youth, education, missions) that I could take, but never took one language (Greek, Hebrew, Latin) class. Personally, I enjoy a little word study, but agree with W. Walker that the average member (without knowledge of the original language) become dependent on the minister to explain everything and can come to the point where they doubt (sounds a little like the Catholics)their own understanding of the scriptures. As mentioned by others, don’t go overboard with word studies, and maybe, don’t mention anything (as you said earlier) unless it is a significant variation. By the way, when members are turned off by the haughty presentation of knowledge, it is not easy to regain them. Some will never forget, some will take a long time to forget.

Justin Rogers

I used to preach directly from the Greek/Hebrew text. I no longer do so. Ironically, although I have now completed a terminal degree which involved the reading of Greek and Hebrew daily, I have reduced the amount of biblical languages I use in sermons. Frankly, Bible class is a more comfortable setting for linguistic enlightenment, in my opinion. While my sermons continue to be heavily influenced by the ongoing study of Greek and Hebrew, my audience rarely knows it.